-

• #377

Yes, I saw that at the time, but the point I was making is simply that, doubts by some scientists as to the current definition of the concept 'species' aside (and I don't say they're wrong), the definition is currently the definition, and the sentences I was concerned with used the concept in such a way that, given its definition, they contradicted themselves.

I wouldn't have any problem with it if someone came along tomorrow and argued convincingly that this definition (and by implication all of biological classification) is impossible, and that there is no way of defining a species accordingly. Someone else might argue that the concept of a species is only a rule and not a principle, which would take the definition involved down a peg (rules admit of exceptions).

I'm interested in archaeology primarily because of its possible role in helping us understand history at a deeper level than before, e.g. what environmental destruction people perpetrated in prehistorical times, or, supposing we were to find much more ancient writing than we previously thought possible, in the times we could subsequently add to our historical understanding, and the lessons we might be able to learn from that. For instance, I think that the desertified areas of Eurasia and Africa most probably were accelerated in their decline by unsustainable human activity, and that ancient populations were much larger than we realise today. In this case, I think there's potentially a useful lesson about racism--much of the narrative about the 'primitive' Neanderthals was created in the 19th century, when there was all this rubbish about 'scientific racism' around to justify colonialism, etc.

I think that humans are humans. They diverged into different branches but could evidently still partner up and have fertile offspring after long periods of separation. Quite apart from that, I don't think that this static picture of separate populations was ever accurate, but that people have always moved around and mingled a lot. History merely repeats today, even if the migrating groups are closer together, but what I think happened isn't that Neanderthals or Denisovans, and no doubt any other group of humans we may yet discover, went 'extinct' but that in virtue of the larger numbers of members of one group the smaller groups quite simply merged into the larger group by intermarriage. Occasionally, of course, there will have been genocide instead.

I don't find the HG Wells quote very interesting, by the way. Of course there are many different kinds of chair. Still, everyone can recognise a chair, even if it's fungoid-shaped or something like that, because it's a very simple concept that we all develop very early; the word 'idea' (which has many, many usages) is sometimes used for 'undefined' concepts like that, as opposed to 'defined' concepts. (My own view is that every concept is subject to definition somehow, but that uttering that definition is often difficult, especially, of course, with complex definitions.)

Crucially, despite being simple, 'chair' is not vague and is therefore still useful even though many, many very different-looking objects fall under it. The same could be true of 'species'; we recognise the idea behind it, but, as counter-examples show, not really the definition (or attempt at a definition). If a better definition could be found, which I think is not at all impossible, it could still be useful.

-

• #378

This seems extremely stupid--why remove part of a tourist attraction from a tourist attraction, let alone one of the biggest in the country?

-

• #379

For the same reason Napoleon removed the Luxor Obelisks to Paris and Elgin stole the marbles from the Parthenon to bring back to London. Powerful cultural symbols, and will still be a tourist attraction in Tahir sq.

Total vandalism to the integrity of the wider historic setting they're taken from but then, loads of monuments are quite artfully 'rebuilt' in the first place.

-

• #380

Also, having been to Luxor, they have such an incredible amount of fully intact statuary that they could easily move a few hundred of them without the average visitor even noticing. It’s an extraordinary place.

-

• #381

No doubt, but risking these things in urban pollution is a deeply stupid move. I'm afraid I'm also on the side of trying to leave things in situ as much as possible.

-

• #382

One of my favourite lost cities is Dunwich, for obvious reasons (well, if you know about the Dunwich Dynamo).

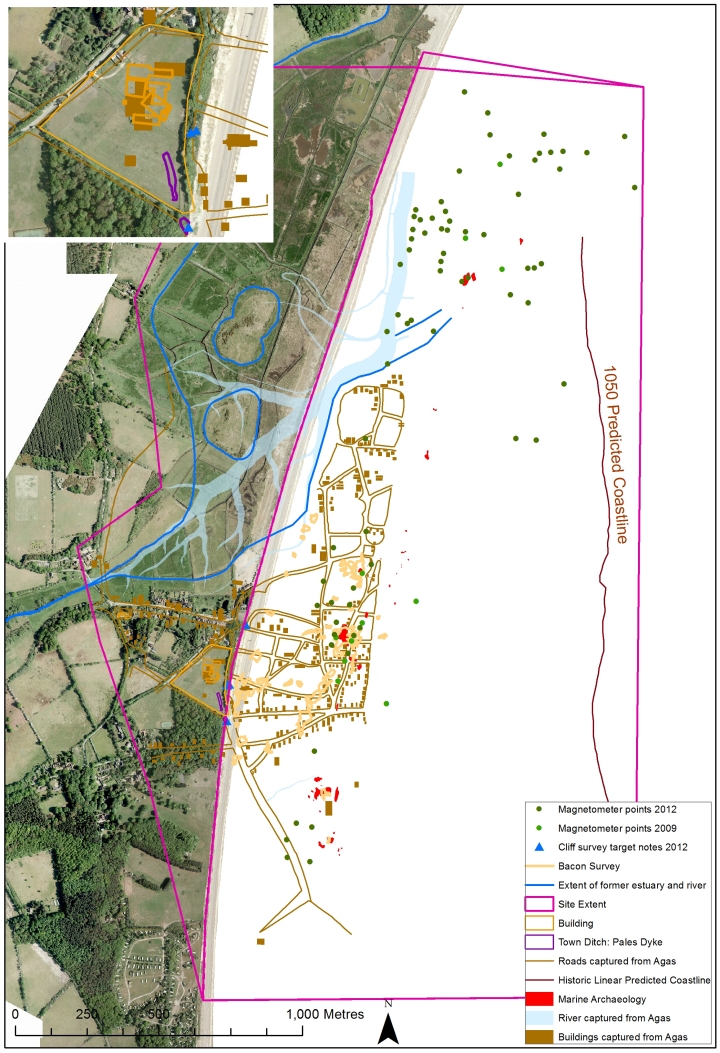

Dunwich was a victim of the (still ongoing) coastal erosion of East Anglia. Quite a lot of its farmland had been lost by 1086 and this is recorded in the Domesday Book. It was finally destroyed enough to be abandoned almost completely in the 14th century, in a series of huge storms, the last of which, the Second Marcellus Flood (or second "Grote Mandränke") also claimed a town called Rungholt in Northern Germany, where the coastline was changed completely and a huge amount of land was swallowed by the waves and turned into mudflats. Rungholt, while apparently smaller than Dunwich, is also suspected of having been an important trading town. Some of its remains have been found, but no attempt has yet been made at underwater archaeology as at Dunwich, because Rungholt was not only flooded but also buried by the mud. Also, unlike Dunwich, Rungholt seems to have been lost completely--in one night, quite possibly with no survivors, reflecting its more precarious position on a low-lying island and the fact that it seemingly was built on artifically raised land. (The method of building artificial hills on which to then build houses to protect them against flooding is still used in the area today, albeit only on a few scattered tiny islands called "Halligen".)

Quite a lot of work has been done to map and remote-sense Dunwich, mainly by researchers from the University of Southampton. There's a web-site which was put up in 2013, but since then they don't seem to have had funding to do much else, and parts of the site no longer work. There's still a decent amount of documentation:

The survey doesn't extend across the whole town, as the eastern end, whose dimensions are still unknown, is buried in a similar way to Rungholt. Even though it was abandoned, some of the buildings of Dunwich were still standing long after the floods had swept away so much, and they were subsequently exploited for building stone and ruined. Gradually, over centuries, erosion caused almost all of them to fall into the sea. The final claiming of various ruined churches is documented, e.g. in the case of All Saints Church, whose gradual destruction is shown in images on the front page of the site above. The last remaining ruins are those of Greyfriars Abbey and the Lepers' Church.

This drawing shows where the cut-off line of the most recent survey runs:

Some of the street pattern of Dunwich can be seen there, and the sonar exploration of the seafloor seems to have revealed a couple of heaps that point to where important buildings once stood, including the 18 churches it's said to have had. When you swim off Dunwich now, you're swimming approximately where the town's landward side once stood. Here's another map:

What I find interesting are the rivers. The river Blyth now meets the sea a little further north at Walberswick, whereas the Dunwich River now flows north-east roughly parallel with the coastline. In former times, the Blyth turned south at Walberswick and flowed towards the Dunwich River, until the coastline was punctured there to give it direct access to the sea. Now the Dunwich River is a tributary of the Blyth rather than the other way around. The reason why the Dunwich River could no longer empty directly into the sea at Dunwich was because the harbour there silted up. This must have been a persistent problem for Dunwich, as much of its prosperity depended on the harbour, but they either lost the battle before the floods, or were still working to keep it open when the town perished.

Long before the floods, when the land would have extended at least hundreds of metres further east from Walberswick and Dunwich, it would have been quite far from both to the sea, probably making the harbour of Dunwich more of an inland harbour, and one less at risk from silting up (which tends to happen to shallow riverine harbours close to the sea).

Thus was lost a city said to have rivalled London, with a population of several thousand (which was a lot for the time), and a city area seemingly larger than that of the City of London.

Dunwich is only one of many, many examples of cities lost to the sea. There must have been hundreds, if not thousands more. As ever, our knowledge of these is woefully incomplete, and remains are sometimes revealed purely by chance:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/ancient-cities-lost-to-the-seas-37942779/

-

• #383

And back to one of my favourite topics, more evidence that 'modern humans' and Neanderthals coincided in Europe for thousands of years:

There will undoubtedly be much more on this in the next few years/decades, but I remain convinced, from what I have seen, that the Neanderthals didn't just 'go extinct' but were gradually absorbed into the (apparently larger) incoming populations, with whom they mingled. No doubt there would have been wars and genocides and all the usual rubbish that humans get up to, but also a fair amount of, erm, love.

One of my theories is that North Africa, roughly where the Sahara now is, was at one point a densely-inhabited hotbed of civilisation (and a fertile part of the world). We haven't found much evidence of that yet, as it's quite difficult to find old stuff in a desert, and because it was so long ago we probably need to dig deeper than we do elsewhere, but when this period ended, quite possibly brought on by unsustainable agriculture and large populations that couldn't be fed any more, there would have been much migration from Africa across the Mediterranean to Europe, as yet not very populated and possessing a distinctly cooler climate than that of the sub-tropics. I think that similar processes probably also affected other areas in Eurasia. Generally, I think that ancient populations were much larger than tends to be estimated today, and that this caused a lot of environmental problems along the way and made large swathes of the Earth uninhabitable or less easily inhabitable.

Anyway, this will be a fertile area for research for a long time.

-

• #384

This is quite a fascinating find:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/22/mexico-city-mammoth-bones-found

I think it's a crying shame that the mammoths are gone; they must have been amazing animals. It does seem likely that here they just fell victim to the treacherous shores of the lake rather than being trapped by people.

-

• #385

Sad loss of what was clearly a very valuable archaeological site, quite apart from its cultural value:

Finding deposits 40,000 years old doesn't happen often in human archaeology and it's inconceivable why this site wasn't protected better. I assume it may be the fact that it's been in continuous cultural use and little archaeology had been done there before, which is a tragic irony.

Even in Australia, where such a long period of human habitation is recognised from finds, I think the date when humans arrived will eventually be pushed back even further.

-

• #387

The key word here being 'after'...

-

• #388

This is pretty amazing: radar used to map a Roman city, collecting 28 billion datapoints https://www.gizmodo.co.uk/2020/06/ground-penetrating-radar-reveals-entire-ancient-roman-city/

1 Attachment

-

• #389

Excellent. This is getting more and more game-changing. You can't publicise this everywhere because of the obvious danger of looting, but I'm sure one thing it's going to reveal (as a similar method already has in Egypt) will be to show that ancient cities were much larger than has been believed for some time. I wonder if/when they'll be able to detect the presence of shanty towns (largely made up of organic materials that decay very quickly, but probably detectable from the presence of middens and inorganic buried objects). I think that virtually all ancient cities will have been surrounded by these and that there will have been a much larger population than commonly believed for cities like Babylon and the like. Places in Italy won't have had shanty towns to the same extent owing to less migration, but they must still have been there.

I'm sure that what's in the diagram isn't the whole of Falerii Novi yet, either (and not only because of the modern buildings). It'll be fascinating to see what contributions this research may be able to make to the re-writing of history. :)

-

• #390

An interesting find in Whitechapel:

This would have been part of London's shanty town (although, of course, a lot of buildings inside the city were also made of wood), as theatres were not allowed in the city. This would have been a short distance from the East Gate, just as The Theatre was a short distance from the Bishop's Gate.

-

• #391

Strange stuff:

I don't know if 'jokes' like that, if that's what this was, make any useful contribution to humour any more.

There is that famous case of the 'Roman' head 'found' in Mexico about which it's still not clear if it was planted at the site at the expense of the excavation leader or if it's a genuine find.

-

• #392

There's a lot to find amazing in this story--that all these sites are getting destroyed, the whole legal context, and how it could come to this.

It's especially sad in Australia, where it's such an interesting question as to when people actually did get there--I'm still convinced that archaeologists are going to continue to find evidence of older habitation. In the case of these sites, the figure of 15,000 years only represents the current state of the research, with further research made impossible by the impending destruction.

-

• #393

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HdsWYOZ8iqM

been binging this type of video recently... very interesting

-

• #394

What do you mean by 'this type'?

Nice little piece of research. Shunting people off land happens all the time, of course, but that's definitely a very interesting case.

-

• #395

A seemingly major new find. I don't understand Stonehenge, so I likewise don't understand this, but it sounds as if the researchers must be on to something.

It does make you wonder whether similar things might not be detectable at other henges, too.

-

• #397

Ah, I see. Be warned that they do unearth cat mummies in Egypt from time to time. :)

-

• #398

I hope this throws a spanner in the works of that underground motorway to kick it into the long grass indefinitely:

-

• #399

A find in Germany near a place called Erbes-Büdesheim of a village abandoned around 1500. No English articles that I can find yet, but here's a German TV report. Warning: don't watch if you don't want to see skeletons:

The main excavation is currently of a graveyard which includes many graves of children, but there are remains of a church and houses. They also think that there was a (much earlier) Celtic fortress there.

As so often, the funding is in preparation for development, in this case an industrial estate. All of the site will be bulldozed when the archaeologists are gone.

-

• #400

Threats to archaeology and site protection funding in Mexico:

Oliver Schick

Oliver Schick kl

kl

ObiWomKenobi

ObiWomKenobi

Annoying pop-up ads aside, this article is quite helpful on this subject -

https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelmarshalleurope/2018/08/28/a-long-busted-myth-its-not-true-that-animals-belonging-to-different-species-can-never-interbreed/#15880eda3e65

I quite like the chair analogy from HG Wells:

"Take the word chair. When one says chair, one thinks vaguely of an average chair. But collect individual instances, think of armchairs and reading chairs, and dining-room chairs and kitchen chairs, chairs that pass into benches, chairs that cross the boundary and become settees, dentists’ chairs, thrones, opera stalls, seats of all sorts, those miraculous fungoid growths that cumber the floor of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition, and you will perceive what a lax bundle in fact is this simple straightforward term. In co-operation with an intelligent joiner I would undertake to defeat any definition of chair or chairishness that you gave me."