-

• #1402

One place in that collection is the legendary Heygate Estate in Elephant + Castle.

Nice. Look how much space there is for all the residents to share:

The Heygate Estate is a large housing estate located in Walworth, Southwark, south London. The estate is currently being demolished as part of the regeneration of the Elephant and Castle area.[1] It was home to more than 3,000 people.[2]

The Heygate is well known for being one of the starkest examples of post-war urban decay in the United Kingdom. Its notoriety has led to it being used frequently as a filming location for music videos and movies.The Corbusian concept behind the construction of the estate was of a modern living environment. The neo-brutalist architectural aesthetic was one of tall, concrete blocks dwarfing smaller blocks, surrounding central communal gardens.

The estate was once a popular place to live, the flats being thought light and spacious,[5] but the estate later developed a reputation for crime, poverty and dilapidation.[6] Residents complained about constant noise, crime and threats of violence. The sheer scale of many of the blocks also meant there was little sense of community.[7] By the 2000s, the estate had fallen into severe disrepair.

-

• #1403

I think this article sums it up rather nicely:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2012/sep/23/stirling-prize-architects-own-homes

The brutalist Balfron, designed by Erno Goldfinger, was built in 1965-67, and for a few scant weeks in 1968 Goldfinger moved into the building himself, the better to convince the world how utterly fantastic his design was (his real home was in Hampstead).

Two things stick in my mind about my visit. The first was the lift, which stops only at every third floor, and was sinisterly long and narrow because, or so our guide told us, it was designed to accommodate a coffin. The second was a debate I had with an architectural historian inside a flat close to the top of the building. Naturally, he was all for Balfron. You should have seen the beatific expression that suffused his face as he urged me to admire its generous proportions, its clever layout, its wonderful view. I was less certain. Would you like to live here? I asked. He insisted that he would. Then he admitted that he actually lived in a Georgian house in Royal Greenwich.

-

• #1404

Has this been summed up rather nicely yet?

-

• #1405

Yes:

Architects need to fully understand the needs of the end users before embarking on new projects.

-

• #1406

And the people commissioning / briefing / developing / procuring / building etc etc etc...

-

• #1407

Excellent.

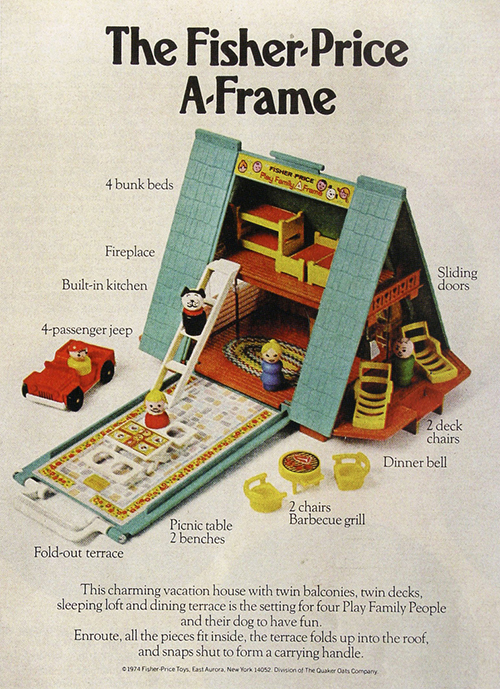

Oh look, an A-frame house!

Wouldn't mind living in one of them one day

-

• #1408

^ My dad's dream domicile.

-

• #1409

nice A-Frame.

Elf- have a look at the likes of Glasgow's Easterhouse estate and Nottingham's The Meadows, then compare to stuff like the Barbican and Highpoint-

as has been said eloquently already, its not necessarily about the architect. -

• #1410

its not necessarily about the architect.

I'm not saying that it always is. I'm merely pointing out failures of architectural design (whether or not that's entirely down to the architects is another discussion). It's not good using places like Highpoint to counter my argument, because Highpoint is about as relevant to a discussion on the failure of many high density social housing projects as involving a pop tune in a discussion of Baroque Classical Music. Highpoint is a small scale relatively low density project intended for a particular type of resident, and has succeeded in it's execution. As for the Barbican; AFAIK that wasn't intended to provide 'social housing', and in fact is now relatively sparsely populated given it's scale (less than 2 occupants per household av.), and caters mainly for affluent City workers, not families. And has already been pointed out, the Barbican is a crumbling behemoth that requires massive expenditure to keep it maintained, and is overdue for demolishun really.

Granted, put the wrong 'type' of people into any sort of housing development, and problems can and will emerge. But such problems are less prevalent in lower density developments.

-

• #1411

There was an interesting documentary on TV a while back (can't recall the name) and highlighted the discrepancies between the planning and execution faces of the majority of high rise buildings in this country. Basically the architects were saying how local councils, contractors and housing associations robbed the British tax payer of quality housing. A lot of them were well designed but poorly executed.

-

• #1412

Nice piece on modern prefabs http://www.fastcodesign.com/1673057/this-prefab-building-is-a-first-for-new-york

-

• #1413

And has already been pointed out, the Barbican is a crumbling behemoth that requires massive expenditure to keep it maintained, and is overdue for demolishun really.

priceless.

-

• #1414

Alexei, don't assume that Barbican isn't a load of shit just cos architects live there.

-

• #1415

The Barbican is very interesting architecturally. And a noble attempt to create the future of housing. Would be absolutely fantastic if you love the arts. And some great details.

http://www.studiomyerscough.com/photos/page_25.jpg

But does it really work as an inclusive housing project? That, I'm not so sure about.

-

• #1416

I don't think the Barbican's that bad.

-

• #1417

Some very good points Elfinsafety. I only wish you would leave the name of the original poster in the quote thus

.

Without it I find all your arguments invalid

-

• #1418

I don't think it's that bad either. It's not a great place for families though (which is why there aren't many living there; go and have a walk round there, it's unlikely you'll see any children out playing). Hence why I question it's inclusivity. It's great for City workers, childless couples, young 'professionals'. Beyond that, I think it is limited. It would work brilliantly as part of a university complex, but that will never happen.

It's showing it's age, physically. And it's getting increasingly hemmed in by the proliferation of skyscrapers being built nearby. It's not the airiest and lightest of places as it is.

-

• #1419

Without it I find all your arguments invalid

I'm playing all the right notes, not necessarily in the right order...

-

• #1420

Eric Morecombe to Andre Previn...

-

• #1421

Well.

I broadly agree with critics of Robin Hood Gardens, the Barbican, and many other post-war housing projects. I do think that the vast majority didn't work, although I of course recognise the places that people were coming from in designing them; the desire to give people more light in their flats than had been the case before, the fact that while today Victorian (and other -ian) terraced houses may be considered the ideal of middle-class living, back then such housing was generally in a poor state, difficult to heat, lacking mod cons, etc. London was also shrinking in population, and planners wanted to loosen up the urban grain and reduce population density, decentralising slightly in the process (although in London this was largely limited to Inner London rather than what we now call Central London). I understand that there was a benevolent imperative behind much of this, but I think it failed due to a number of factors.

(1) The status quo. While there may have been idealistic architects around, there was still little appetite in society at large to really change the status quo.

(2) An excessively theoretical burden in experimenting with new forms. Much of what was tried was completely untested and then failed in practice.

My approach to and discontent with post-war architecture is firstly about the planning context in which they occurred. This was, of course, a 'car is king and the future' kind of context. Le Corbusier's 'theories' have already been mentioned, e.g. the idea of completely separating transport and living functions. This flight of fancy is now discredited almost everywhere, although the idea of urban motorways and ring roads has survived this. However, in practice it meant that where massive roads weren't imposed willy-nilly, leading to the destruction of large residential areas or cityscapes (as at the Westway), developments were built far back from the carriageways in order to later widen the roads when all old houses had been knocked down (which generally never happened). Developments were almost never positioned in such a way as to still have a relationship with the surrounding streets, e.g. being placed at odd angles. Vehicular access entrances, basement car parking, or other ugly services located at ground level served further to alienate people both from the streets and these buildings.

Another problem that for me comes first, long before I start to think about the style of architecture, is what I call '(contiguous) secondary networks', which a lot of new housing estates bombed into the existing primary network. I happen to believe that the simpler and the more readable you keep the primary network, ideally without any disruption from secondary networks, the better.

Many estates became self-contained no-go areas not because of screaming tabloid headline exaggerations, but because of the way access to them was offset from the 'old' network, because movement through them was actively discouraged by designers, because many were designed around car traffic only, or because, as in the Barbican, the attempt was made to have all traffic on foot circulate at first floor level (as per the Buchanan Report 'Traffic in Towns'). Many other examples of failed design ideas which led to the creation of secondary networks could be adduced.

The way in which a building, which even if public is largely impermeable, relates to the primary network of streets is an absolutely key consideration in design, long before any details or architectural styles are applied. When I look at RHG, I see a disconnected relic of a bygone age whose assumptions we don't share any more. Some people, I'm sure, would still today love the idea of 'streets in the sky'; most of those, however, who have lived on them, probably wouldn't, as it relied excessively on mere theories.

I like strong streets with lots of entrances so that there is activity, with small(ish) units, with a good mix of uses and buildings on a human scale, as part of a clearly-defined public realm that has a good mix of intimate streets and large(r) public spaces and clear rules for their use, as well as a lot of green.

I dislike intensely excessive concentration of functions, monocultures, confusing and disconnected secondary networks, blocks to permeability, layers and layers of variations of rules on how to use them (e.g. contiguous secondary networks on privately-developed estates like MORE London with their ban against cycling). I don't like tower blocks because I see them as built images of injustice.

So, blaming the architects is undoubtedly appropriate in some cases, but by far the more dominant factor was the spirit of the times, what people thought was good and future-proof and which proved not to be, and that was really motor traffic-centric planning. Many undoubtedly worked with the best of intentions, but the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

As ever, far more could be said on this topic, etc.

-

• #1423

Excellent.

Oh look, an A-frame house!

Wouldn't mind living in one of them one day

I used to have one of them.

-

• #1424

Any RICS members on here? I'm doing my "professional experience route" to membership at the moment. Probably got for my APC next summer.

I've also been dropped in the deep end with my first big civil construction project after ten years of quite niche railway specific engineering. It's interesting but a daunting learning curve. Just wondered if ther ewere any other QS' on here?

Elfinsafety

Elfinsafety kboy

kboy Prole.

Prole. withered_preacher

withered_preacher jaw

jaw Aleksi

Aleksi Skülly

Skülly handtightenonly

handtightenonly dst2

dst2 Oliver Schick

Oliver Schick hoefla

hoefla bq

bq dooks

dooks Rich_G

Rich_G

@coppiThat

@coppiThat

@ Elfinsafety: They are similar in needs and constraints. Both are big cities where the majority of citizens can't afford to buy for one reason or another.

In case you're interested, this article sums it up rather nicely.