-

• #2

Most people have a good understanding of the history of the 996 - it was launched with a development of the water cooled flat six from the Boxster, pushed to 3.4 litres, but the decision was taken to install a water cooled evolution of the older air-cooled motor to create a high performance version that would be called the GT3. The same engine also appeared in the turbo, and the Porsche Cup cars (with changes appropriate to each, of course).

Slightly less well known is the X51 Powerkit, a comprehensive upgrade package for the M96 engine that was created when Porsche was evaluating whether the M96 had what it took to be the base engine and the high performance version.

For the 996.1 this kit was extremely comprehensive, encompassing an additional oil scavenge pump, heavily revised sump, X51 specific heads, pistons, cams, valves, a whole new cast aluminium intake (instead of the stock plastic unit) and much larger diameter exhaust manifolds, an additional central radiator and a revision to the DME to manage all the changes. This wasn't a red badge and a tweak to the map - the engine was gone through from top to bottom and almost every system was revised or enhanced.

And, of course - it wasn't enough. The decision was made that the Mezger was the way forward and the rest was history.

The X51 kit continued to be offered, but with each subsequent iteration it was less comprehensive, and whilst certainly more than a trim level it was never as comprehensive as it was in its original form.

Over the years the M96 has become the butt of many jokes, the chocolate engine, the engine Porsche wanted to forget, and with the move to the 9A1 architecture it largely was.

I have to admit though, I liked it - characterful, makes a great noise with a sports exhaust, plenty of shove low down but some real zing in the upper reaches of the rev range. I had bought my 996 on 60,000 miles, and decided that I was going to run the engine through a prophylactic Hartech rebuild before it hit 100,000 in order to preserve all the things I liked, but remove the weaknesses that were well known to bedevil the M96 (and some that were less well known, but still needed to be engineered out).

Around this time Matt Falks had the engine in his very well known 996 C4 rebuilt, in his case by Autofarm, and pushed to 3.7 litres.

He was good enough to publish some estimated power power and torque plots for his revised engine, and it was clear that the new unit had more horsepower and torque- both delivered lower down in the rev-range.

This was clearly a strong indication that when I got my engine rebuilt I should swap from the 96mm bore to the 100mm bore in order to take my 3.4 to (the obviously much more desirable) 3.7.

But, why stop there? It occurred to me that if one were to add the X51 kit to the 3.7 then it's higher lift cams, flowed heads and increased rev limit might create a unit that continued making power when standard 3.7's were already changing gear, an engine that potentially answered the question "what if Porsche didn't choose the Mezger?"

I started to put together a wish-list for my new engine, a list that could be summarised in two key points: remove the weaknesses of the M96 and add drama in the form of revs and power.

First, the weaknesses.

-

• #3

I'd never thought of using anyone other than Hartech to rebuild the engine - their knowledge of the M96 is unparalleled, and Baz Hart is an extremely talented engineer and (rather helpfully) a very nice chap. I spent ages on the phone with both Baz and Grant, and their willingness to share their knowledge really made this project possible. Hartech race the M96 engines and have developed fixes which address the weaknesses exposed by both road and track use - incredibly useful empirical knowledge of the engine, won the hard way.

Now, the M96 has an intermediate shaft that runs beneath the crank and transfers power to the cams via chains, and the oil pump via a 50mm hexagonal key. It's got an oil fed plain bearing at the oil pump end, and at the other a sealed bearing - the infamous IMS bearing. This is the beté noire of the M96 according to Porsche folklore, and it's said to be simply a matter of time before it destroys every engine in which it is found.

This isn't quite true, and anyway for the new engine we'd use the final development of the IMSB from the M97 - a much larger bearing than used in the 996 versions, so large in fact that it can't be installed or removed without splitting the engine cases.

Next on the list was crank flex- the construction of the M96 is such that the crank has a marked cantilever from the final main bearing to the flywheel, and this, when combined with vigorous use of the clutch and revs can flex the crankshaft, leading to rapid wear of the main bearings, leaking Rear Main Seals (RMS) and - in extremis - snapped crankshafts. Hartech offer an EN40B crankshaft (which a good friend who joined me in the project chose for his engine, more on this in due course) and also they can machine the engine case and install an additional bearing just behind the flywheel which constrains the degree to which the crank can flex, and essentially removes this problem.

Now, I was determined to spin the engine past 8,000 rpm - I wanted fuel cut at ~8,500. This meant we had to look at the valve train, and by this point a chap from 911UK who has an incredible knowledge of racing engines had offered his assistance. We quickly identified the tappet chest as a weak link, for numerous reasons.

For one, it was cheap crap - a weak casting with the bare minimum of material required, and was known to suffer from hydraulic fracturing in normal road use. As new camshaft blanks were not available for the M96 we'd also need to re-grind stock ones, hence would have a smaller base-circle, which would mean that the tappets would ride higher in their bores, and would need both more support and the oiling hole position changing.

It was clear that we needed a new tappet chest, as we simply couldn't modify the existing one to meet our requirements. By this point I'd managed to infect another chap from 911UK with my obsession, and he'd decided to build not one but two engines to our new "X51 Cup" specification, and very rapidly it became apparent that without his input we'd have got nowhere fast.

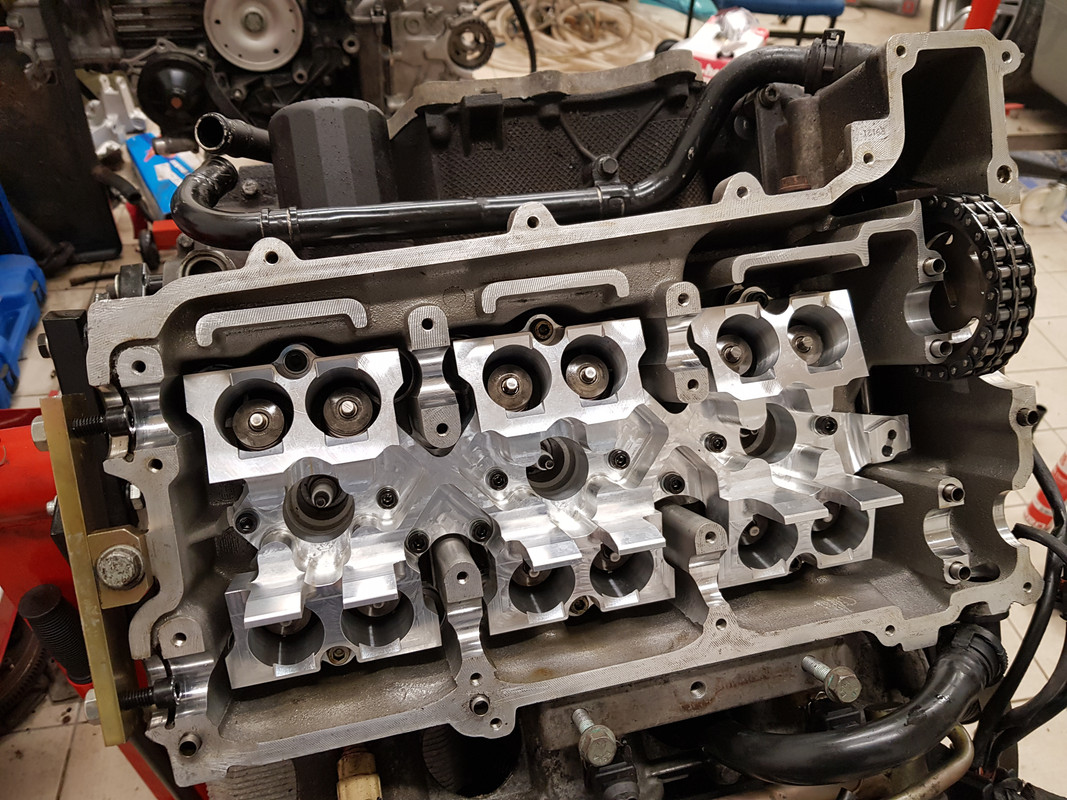

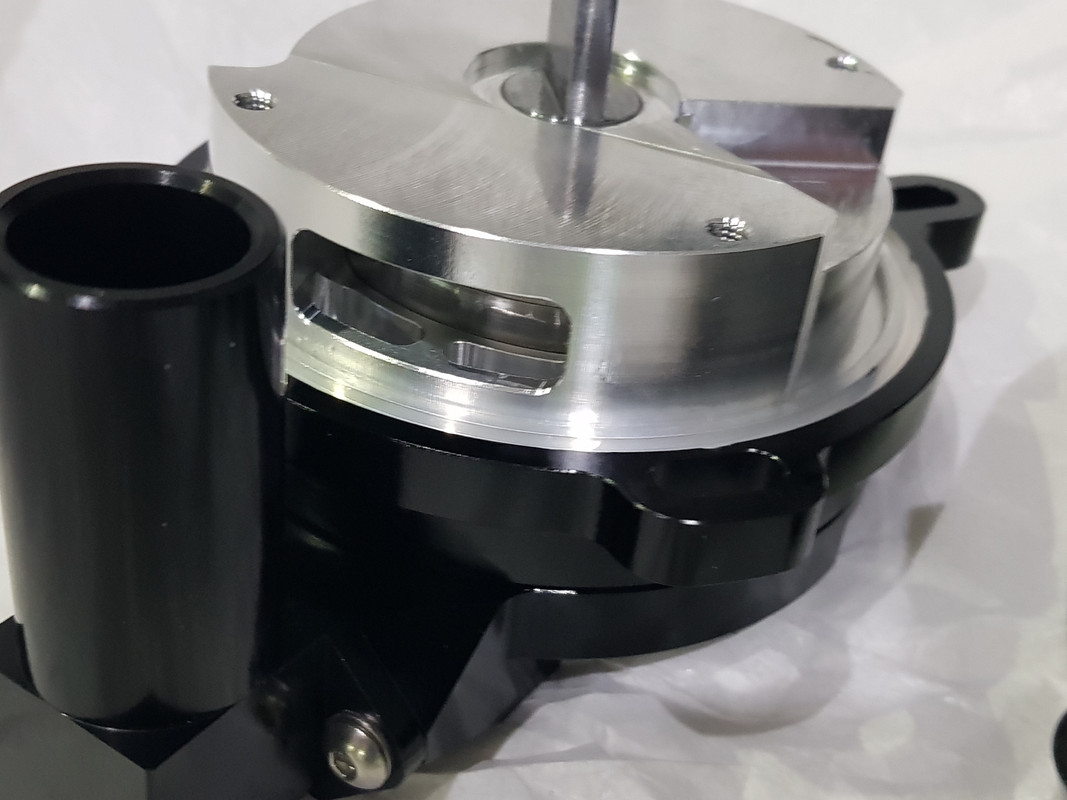

We ran a stock tappet chest through a scanner, creating a highly detailed (and enormous) digital image of it. My partner then created a CAD model from the digital image, and in consultation with the engine designer we created a new tappet chest that addressed the weaknesses of the OEM one. I emailed Richard Brunning (of Bad Obsession Motorsport fame) and asked if he had a recommendation for a machine shop that could do the work - step forward Specialist Engineering, who created this prototype for us:

-

• #4

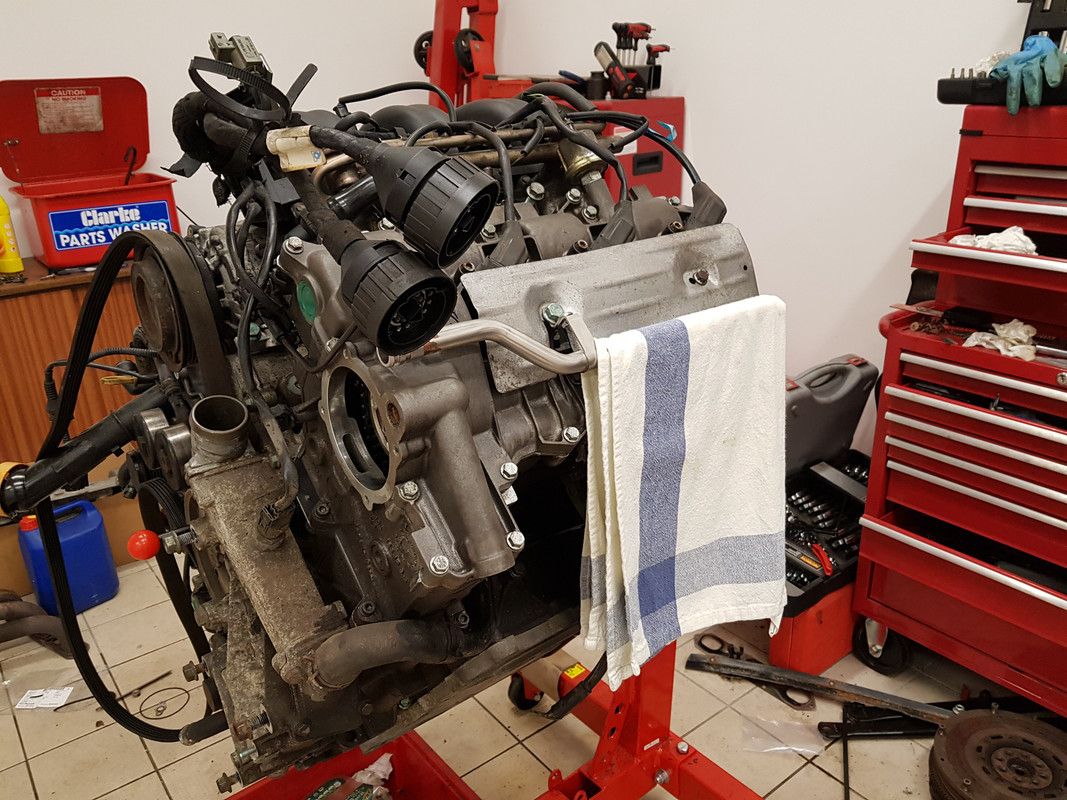

Finally, the oiling system - an integrated dry-sump in Porsche speak, disparagingly called a wet-sump by almost everyone else, but actually somewhere in-between.

In it's stock form the integrated dry-sump tank is formed from a plastic baffle that sits in the centre of the sump, and whilst the engine is in operation the oil is returned to this internal tank. Sadly, the tank isn't exactly oil-tight, and under heavy G the oil can escape into the rest of the sump. This is largely resolved by fitting the X51 sump which has an aluminium baffle/tank with rubber seals that fit tightly against the internal walls of the sump and do a much better job of keeping the internal tank full under G. This just left the issue with the heads - or, rather, the right hand head (as you look at the car from behind). To save money Porsche used the same casting for both heads, so the drive end of the cams is at the back on the right, and at the front on the left. Each head has an oil scavenge pump that returns oil to the central tank/sump, and under normal conditions this works fine.

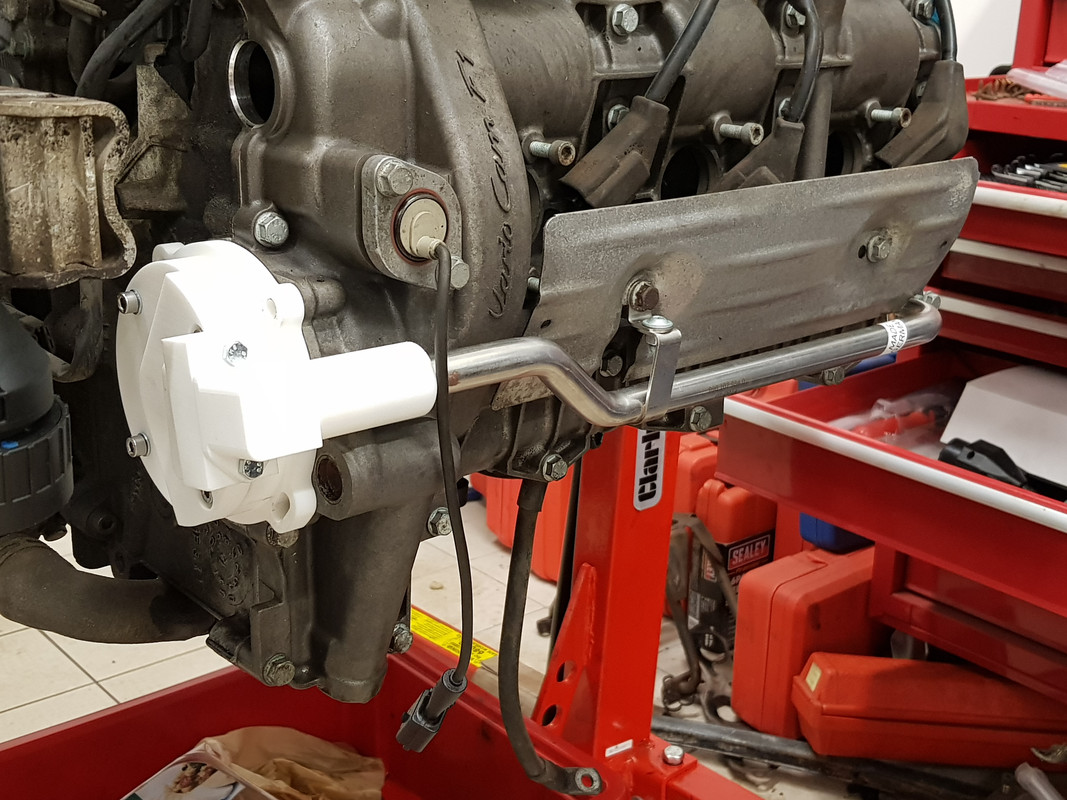

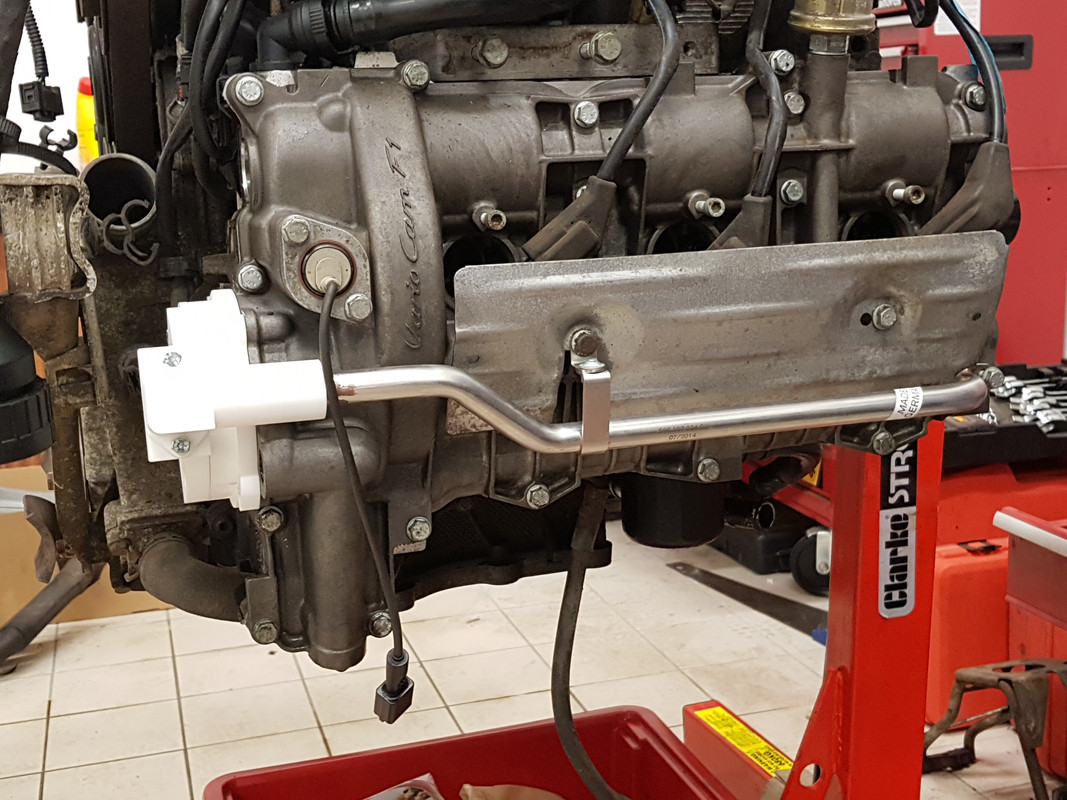

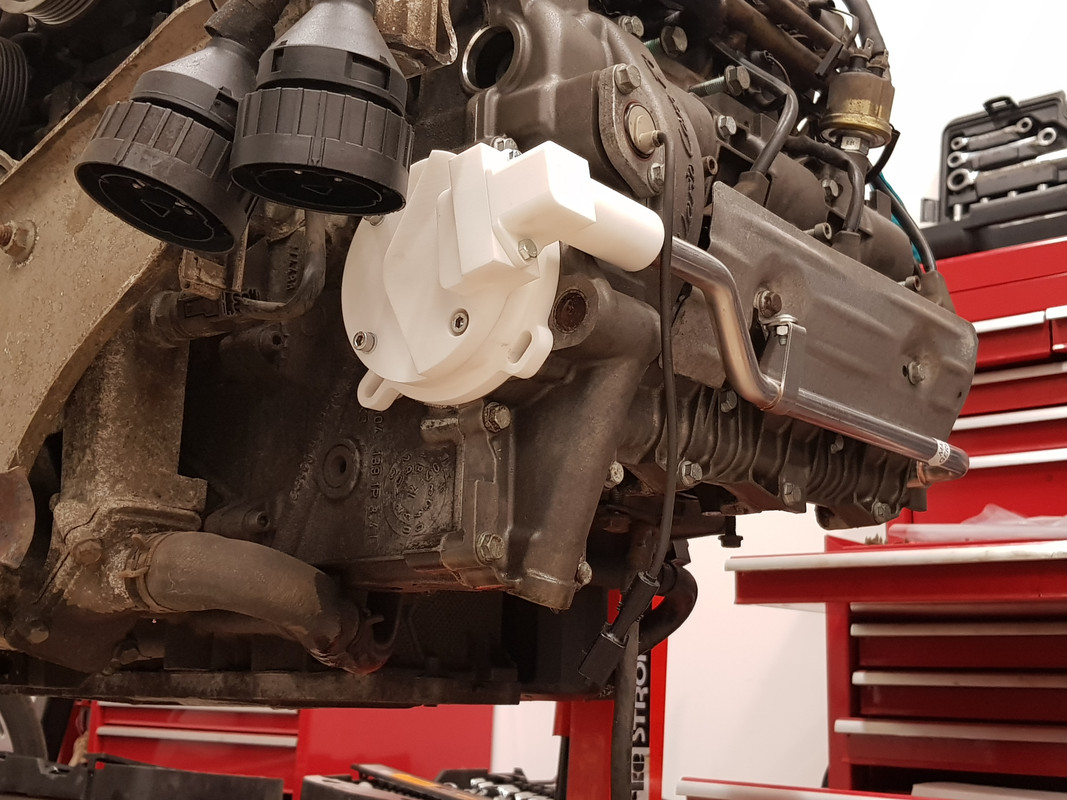

However, under heavy braking, and especially if the car is turning left, oil pools in the front of the right hand head as the scavenge pump is at the back, and for that brief period is sucking air. Porsche resolved this by fitting a dual stage scavenge pump to this head that scavenges the front of the head via a port on the cam cover, to which it is connected via external hard-line (the iconic X51 towel-rail). So - buy the dual stage pump and problem solved, right? Sadly not - the currently available dual stage pump spins backwards, which we considered to be sub-optimal. So we made our own:

Leading to:

-

• #5

With the weaknesses taken care of we had to think about how we were going to get enough air through the engine. I had purchased an X51 intake, but it soon became apparent that an intake optimised for a 7,200 rpm wasn't going to cut-it at 8,200 rpm. I sold the X51 intake having never taken it out of it's box - losing a mere £500 for the privilege of having it on a shelf for six months.

With the decision taken there was only really one choice - individual throttle bodies had to be the way forward.

We had a look at what was available - a choice of one, essentially, with Jenvey making a kit. We decided to go our own way, and started adapting some BMW M3 ITB's:

https://i.postimg.cc/qBWJsxRp/2020-01-13-08-01-36.jpg

Initially our thinking was to use the variable length centre section from the later 4.0 RS as a plenum to feed the ITB's:

But we may go with ordinary ram-pipes initially, more on this as we continue to develop the intake side of things.

-

• #6

The heads have been extensively ported, and the results on the flow bench were very promising, however Mike was convinced that the geometry of the valve seats was holding us back. New, larger valves (paired with titanium retainers and new, stronger double valve springs) allowed him to re-profile the seats for another significant increase in flow.

-

• #8

Bore and stroke - the standard 3.4 engine has a 96mm bore, and the Lokasil liners are an open-deck design which ovalise over time.

They can be fitted with reinforcement rings, but a better solution is to machine them out and replace with Nikasil liners, and whilst you're there close the deck.

And, if you are machining out the liners and replacing them - why not go for a little extra displacement?

Initially I was going to use my existing 3.4 litre engine, but as development went on I was made an offer on a brand new 3.2 litre (Boxster S) block that was impossible to refuse. The 3.2 is identical to the 3.4 in every dimension that mattered for me, and the new 100mm liners combined with the 3.4 crank yielded 3.7 litres. Martin decided to build a 3.7 for his existing early 996 coupe, and a 3.9 (using a 996.2 3.6 litre bottom end) for his new project car, a 996.1 C4 converted to RWD.

New 100mm pistons matched to the new bores:

And three fresh engine blocks waiting to be built up:

We need to finalise our con-rod dimensions and get them ordered, then we can assemble an engine and run it up on the dyno.

We're so very close now - but there's still so much to do.

-

• #9

Gearing - the standard box has pretty long ratios, adding ~1,000 rpm to each gear would make them intergalactic.

Also, the engine is going to come on cam from around 4,000 rpm, then scream past 8,000 before fuel cut forces you to grab another gear.

Long gears are not going to work here - they'd take forever to get into the power band, and when you change they'll drop you out of it again, a recipe for frustration.

The stock box is, frankly, somewhat of a pain here- it requires a fairly hirsute press to get the gears off the shafts, and of course back on again.

Albins (in Skippie-ville) make gearsets which can be swapped in, should you have an Esau edition press in your workshop, and said gears are helical so should be fairly mild mannered.

There is also the option of straight cut gears from the likes of Guard, but I'm uncertain that I could cope with the noise (beyond what would undoubtedly be the hysterical first drive).

We did look at using the GT3/turbo box, but the different dimensions make this very difficult (and conversations with companies such as Quaife revealed that they'd tried and failed to convert their Cup box to work with M96 variants), so modifying the stock box appears to be the way forward.

Current plan is to dyno the engine, then extrapolate the required ratios from the shape of the curve that we get, in order to drop into the power band each time another gear is selected, then order a stack of suitable gears from Australia.

Somewhat undecided as to whether it would be a good idea to make the whole box very short, or leave sixth as a much longer gear for cruising on the motorway.

-

• #10

Cams.

The 3.4 litre M96 engine has four camshafts, two per bank, with the exhaust cam being driven from the intermediate shaft (yes, that intermediate shaft) via a chain.

The inlet cam is driven from the exhaust cam, again via a chain - the tension on the chain can be varied, which changes the inlet cam timing. This is called VarioCam, a simple system that has an annoying appetite for the (expensive) actuating solenoid.

Unlike more sophisticated systems there is no variation in valve lift with this system - that came with VarioCam+ on the 3.6 litre engine of the 996.2.

In the X51 package for the 3.4 Porsche changed both inlet and exhaust camshafts, interestingly the earliest engines came with lash caps whilst the later ones featured longer valve stems (valve diameters remained the same).

With the 3.6 X51 package Porsche elected to only change the exhaust cam, the inlet now having variable lift courtesy of the "+".

We had a good look for the lift and duration of the X51 cams, but the paucity of information (Porsche themselves were totally unwilling to provide any data) combined with the cost prompted us to look elsewhere.

No one makes cam shaft blanks for these, and billet cams are a) expensive and b) accelerate wear in the valve train.

That left us with Schrick cams, or re-grinds. First we looked at the Schrick offering and, whilst it was interesting, we weren't a fan of some design elements and also decided that having a grind that was 100% orientated around our requirements was the optimal solution.

This does mean reducing the base circle, but we have our billet tappet chest (so we can adjust where the upper edge of the bore of the tappet is relative to the centreline of the cam, and the oiling) and our own valves (as we upped the diameter for both inlet and exhaust) so this has been accounted for.

At the moment the thinking is to have three options - fast road/track/race, but I suspect we'd be unable to resist the temptation of fitting the lumpiest cams with the highest duration. We'll see - the cam designer can grind to order, so we don't need to make our minds up until quite a late stage.

The cams in the 3.4 are shared with the 3.2 Boxster S, so when in a 3.7 (my car) or a 3.9 (Martins) they're a significant limiting factor, therefore this was an important thing to get right.

I think three of the things that we paid the most attention to were valve and valve spring material, weight and form, every aspect of which then informed the cam design. I'm reliably informed that valve train float is A Bad Thing, so attention here is important.

Anyway, suffice it to say that whichever of the three profiles we end up putting in the engines the valves will open further, for longer.

Interestingly this has knock on effects in other areas - the Porsche exhaust cams are (relatively speaking) rather inoffensive little things, so choice of exhaust manifold design doesn't really make a huge difference. Moving to rather spikier cams means that we now need to optimise the exhaust for the cam design, so equal length primaries become important, although we're constrained by the packaging when it comes to primary length (there being a finite amount of room between the underside of the engine and the road), still we should be able to get a decent amount of tube under there.

-

• #11

Remember the hard top in the first couple of pictures? I bought a wall mount and a cover for it, and I've never fitted it again since that first winter:

-

• #12

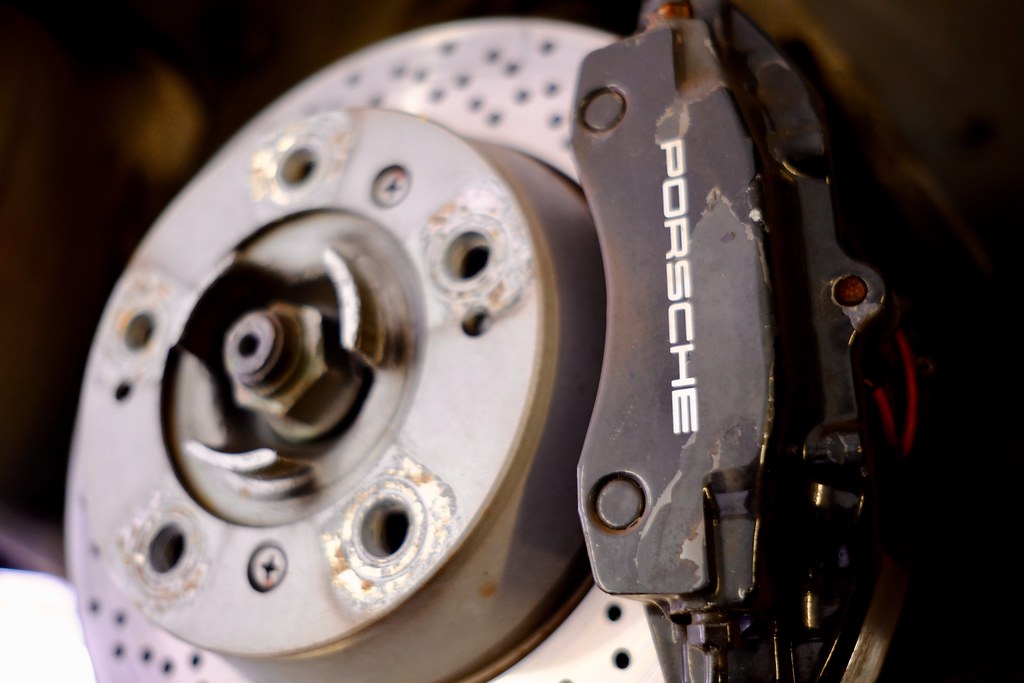

What's the use of go, if you can't turn? I decided to fit Ohlins R/T fully adjustable coil-overs.

We checked the old geo before stripping the old suspension off, it was, erm sub-optimal:

-

• #13

Wow... this is even more insane than I realised from the car thread... this is the most under-stated total rebuild to a vision that was never fully realised that I've seen.

Impressive stuff Dammit.

-

• #14

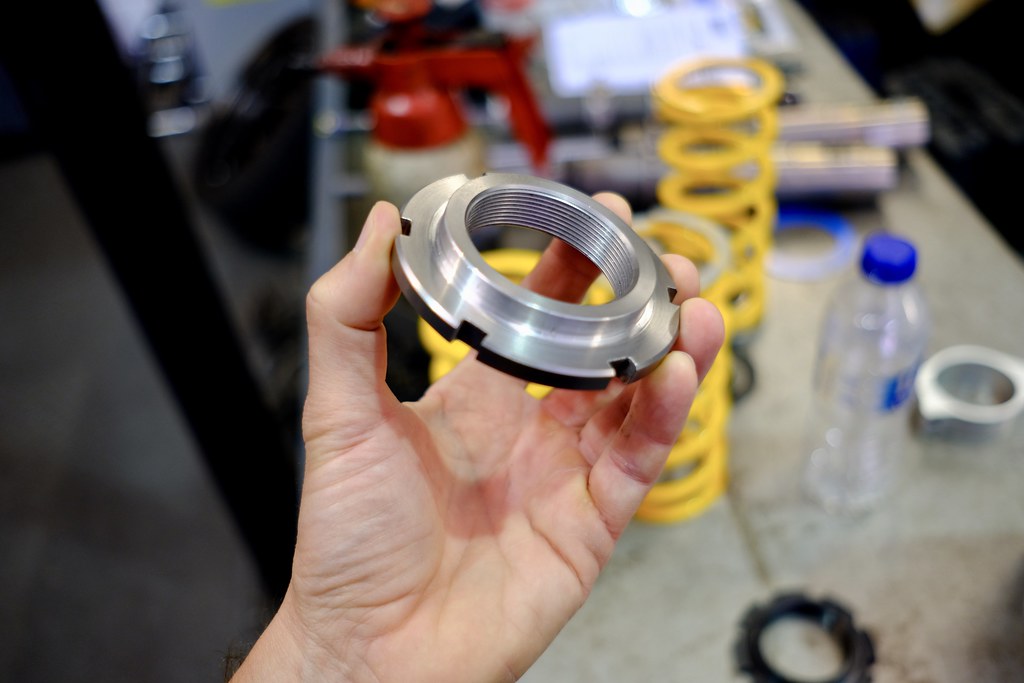

We had to turn down the Ohlins spring perches by 2.5mm, once done we could get on with fitting the new suspension.

Remote adjusters for the rear shocks:

Old stuff (actually new, I'd replaced it in the first service - d'oh!):

-

• #15

Fantastically outrageous!

-

• #16

The geo we ended up with, this may change to fit the new wheels in (more on those to come):

118mm at the front:

135mm at the back:

-

• #17

Here's the old ride height, it's now 30mm lower than this (and about to go lower):

-

• #18

Now, I'm just under 6'2", and the car was clearly not designed for someone my height - which I thought was a little odd as frankly I'm not that tall, but there you go.

With the seat back as far as I could put it and still hold onto the steering wheel my inner thighs were hard against the steering wheel, and in the case of my left leg my shin was hard against the lower centre console. I deleted the lower console which made a big difference, but the angle that the wheel held my leg in meant that my left buttock went to sleep after an hour of driving the car - which meant I had to get out and do some stretches and enjoy some dramatic pins and needles as blood flow returned.

I needed a wheel that was closer too me than the Porsche one would do - enter the Porsche Cup wheel:

-

• #19

The photograph was taken from my eye level - spot the problem?

-

• #20

Don’t need to see your speed anyway, and you should be able to feel the revvs

-

• #21

Now, the 996 wheel doesn't adjust for rake, so in order for me to be able to see the top of the dials it meant that I had to go down in the car.

That meant that my hard backed sports seats, which I'd had as a condition for buying the car and had then had the backs painted body colour, would have to go.

-

• #22

Now I'd fitted a fire extinguisher to the passenger seat, and it'd been such a mission to find all the NLA OEM parts I wanted to keep this side as it was:

Option M509 in case anyone is into old Porsche fire suppression systems.

-

• #23

“See the problem?”

Lick your finger and hold up to gauge speed instead

-

• #24

This is tldr as fuck but I want to read it all! Gonna have to schedule some time in later!

-

• #25

Enter the Recaro SPG:

Which as you can see is much lower than the stock seat, and frankly this was a revelation - for the first time I was sat down in the car, I could see all the dials, my driving position was literally spot on. However, the bucket seat also held me precisely in place, so for the first time I could feel exactly what the car was doing in a corner - this resulted in me going around roundabouts much faster than I had before, whilst laughing a lot.

Dammit

Dammit Shandoom

Shandoom Velocio

Velocio Colm89

Colm89 Jonny69

Jonny69

A few years ago I reached 40, so I bought a Porsche 911 - it was that or have an affair with a colleague, and Aaron wasn't willing.

I wanted a specific model, which I almost ended up with. Specifically, I wanted a 996 Coupe, as that was the current model when I became interested in cars, back in the mid to late 90's.

The 996 was produced from 1997 - 2005, with a facelift halfway through the run, earlier cars are typically referred to as 996.1, later cars as 996.2. Porsche produced a variety of body styles, powertrains and levels of tune which resulted in a lot of choice.

However, what I wanted was the earliest car I could find, a manual coupe with amber indicators, cable throttle (as opposed to an electronic one), a three spoke steering wheel and hard backed sports seats. I spotted what I thought was a great example of this, which belonged to a chap who worked in Selfridges - the car was parked in the Selfridges car park and my office was around a 20 minute walk away. When on the phone to arrange this the seller pointed out that it was a cabriolet, which wasn't what I was after - but it was lunchtime, it was sunny, I thought why not so I went to see it.

We took a test drive around Regents Park - very sedate, but huge fun, in no small part due to being able to drop the roof. I was sold on the idea of an open car on that drive and decided that this was a nice little car, and more importantly I liked the owner and felt that I could trust him (I'd been to see other cars that I very definitely could not say the same about).

We arranged a price, and the seller offered to drop the car into the garage that his boss used to perform a pre-purchase inspection, just for peace of mind. When he'd handed over the keys they called me, I paid over the phone and they went over the car. The result? £4,000 or so of work listed.

I have to admit that I was going to walk at this point, but the seller said "look, not that I know the car needs it I'll have to get it done before I could sell it to someone else, so I may as well reduce the price by that amount if you still want it?"

Faced with such a reasonable offer I paid £9,500 for the car, drove it home and very, very carefully reversed it into it's new home.

The next morning I drove it to Precision Porsche for its first service.

Now, originally I was planning on keeping the car 100% stock, and just bringing it up to as close to a concours condition as I could stand maintaining. That changed.